A sense of mystery gathers around London’s lost rivers, with their names whispered like forgotten deities from an ancient cult. Fleet, Tyburn, Walbrook, Effra, Westbourne, Neckinger.

In some cases, they aren’t so much lost, as buried. Sometimes, they break ground, appearing where you least expect them. Take the grey duct that carries the Westbourne above the District and Circle line at Sloane Square as an example. Yet the Walbrook seems truly lost. As Tom Bolton says, it “is the most mysterious, elusive and comprehensively buried of London’s lost rivers” (2011: 117).

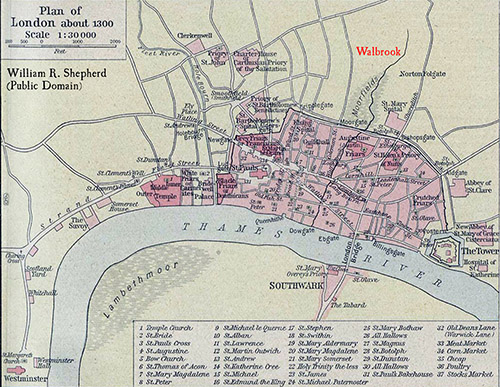

The Romans chose to found London where the Walbrook met the Thames. The river formed the eastern boundary of the first incarnation of Londinium. The Romans also built a Temple of Mithras beside the Walbrook. But even by the 1st century CE, writers described the river as choked with rubbish. By 1463, the authorities built over the last open stretches since they were so choked with sewage (Bolton 2011: 117).

It seems unforgivable that our waterways risk returning to such a state here in 2025. But I digress.

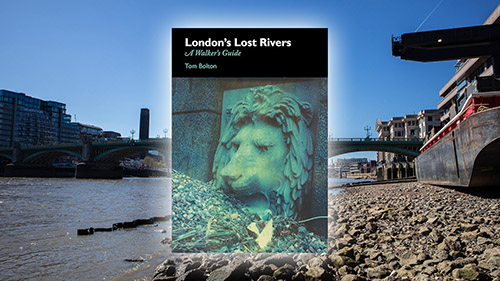

While I was in London at the beginning of April, I decided to trace the route of the Walbrook using London’s Lost Rivers: A Walker’s Guide by Tom Bolton (affiliate link). Well, as best as you can, given the entire river is underground. Given the lore surrounding these lost rivers, I decided to share my expedition here as a form of folklore-meets-psychogeography. Let’s see what we can learn both from the river, and the history of the London that overlays its route.

The Walbrook Source

The name ‘Walbrook’ could come from the aqueduct that carried the river through the Roman wall into Londinium. Others think it could come from Weala Broc, or ‘brook of the foreigners/Britons/Welsh’ (Bolton 2011: 118). I can’t help thinking Roman efficiency probably wins the day here.

Most writers cite Shoreditch as the source of the Walbrook. In the Curtain Road area, you see various signs for a holy well. Now itself lost, the holy well gave its name to a medieval priory. Its grounds covered Bateman’s Row, Curtain Road, Holywell Lane, and Shoreditch High Street. No one knows where the well stood, and it disappeared from maps in the 18th century. The best you’re going to get is New Inn Square. It’s a dead end at the bottom of a decidedly unglamorous back street.

Yet this area was once far more famous than it is now. In 1576, James Burbage built The Theatre for the Chamberlain’s Men, William Shakespeare’s company, among the Holywell Priory ruins. Excavations revealed its foundations in 2008. It seems theatre builders chose Shoreditch because it fell outside the City of London, and beyond the censorship of the City fathers (Bolton 2011: 120). In 1598, they dismantled the theatre and rebuilt it in Southwark. You might have heard of it – they called it the Globe.

In those days, Curtain Road marked the City’s northern boundary. Finsbury Fields lay beyond, stretching to Moorfields, which became a plague pit in 1665 (Bolton 2011: 120). Curtain Road took its name from the Curtain Theatre in the area, having been previously called Holywell Street. It also heads south towards Liverpool Street Station, taking us away from the Walbrook’s apparent source.

Arts and Crafts En Route

Where Curtain Road crosses Worship Street and becomes Appold Street, it’s worth looking west along Worship Street. You’ll see a row of buildings designed by Philip Webb, the Arts and Crafts architect. You might not know his name, but you’ll probably know one of his friends – William Morris.

This row is 91-101 Worship Street, and is a Grade II* listed building. Built in 1862, they were originally workshops and homes for artisans, with the idea craftspeople could live above their workshops. It’s likely that the block only got the Grade II* listing because of Webb’s status (Draper 2013).

They’re not exactly outstanding examples of architecture at first glance, lacking the kind of ornamentation you’d get with Gothic Revival. But they’re important because the intention for the buildings to house artisans and provide workshop space is true to Arts and Crafts principles. This was the movement that arose in part in response to the industrial revolution. It sought to return the human to the manufacturing process. Items were often imperfect precisely to prove the involvement of human hands. It also explains why the buildings were apparently slightly unfinished inside (Draper 2013).

Entering the City

The next stage of the route is, quite frankly, rather dull. Appold Street is lined with the type of buildings you get in the City, with all the depth and personality of a puddle.

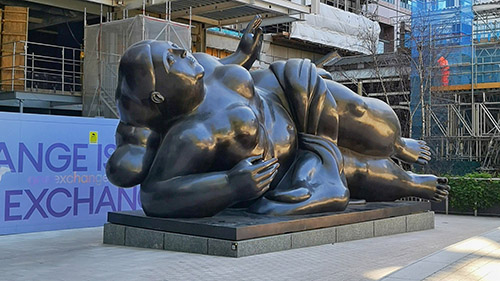

I actually took a detour from the route and wandered off into Exchange Square, a wonderful green oasis at the back of Liverpool Street station. The station announcements take on a peculiar quality as they echo around the square. Still, families played in the fountains and dog walkers enjoyed the patch of sun. Here you’ll also find the Broadgate Venus.

While it might seem from this blog that I’m quite the fan of goddesses like Juno or Minerva, I do have a soft spot for Venus. When I spotted this huge sculpture by Fernando Botero on Google Maps, I felt I had to pay a visit. Commissioned in 1989, Venus weighs five tons and she’s made of bronze. I love the fact that Botero has given her the kind of voluptuous curves that you normally don’t see celebrated in art. Given Venus’ patronage of the arts, I think she’d approve.

Centre of Commerce

I eventually wandered back onto the route to pass through the Broadgate Centre, the shopping mall to the west of the station. Broad Street station once stood here, and before that, the site held the Bethlem Burying Ground for the nearby Bethlehem Royal Hospital. The burial ground opened in 1569 but also served as a plague pit. Excavations in the area during the Crossrail project found six bodies per cubic metre under neighbouring Liverpool Street station (Bolton 2011: 122).

The Walbrook ran beside Broad Street station and is now believed to flow beneath Broadgate Circus. I paused to take some photos and wondered how many of those enjoying lunch in the sun realised what once lay beneath their feet.

My next stage took me down Blomfield Street, at which point one of my dearest friends had come to join me for this Fabulous Folklore adventure. While it’s now a street typical of the City of London, too narrow with tall buildings that hem in any passersby, it marks the old site of the Moorfields. This was an open, fen-like area that people treated much as they treat the parks now, as somewhere to walk, although they also used it for archery practice and hanging out washing (Bolton 2011: 123). Those last two activities might raise an eyebrow now. The Moorfields also became a vast encampment for those made homeless by the Great Fire in 1666.

Landlords emptied latrines directly into the Walbrook here, so we can only imagine how filthy the river was at this point on the route. It flowed onwards in its aqueduct through the Roman wall at the point where Blomfield Street meets London Wall. Builders found remains of the aqueduct in 1840, still covered in moss (Bolton 2011: 123).

It’s Bedlam Round Here

London Wall still looks like a wall, yet at one stage, the site was home to the Bethlehem Royal Hospital. As much as I could talk about this deeply sad building for hours, it’s not our main focus. But it’s worth a tangent since it was important to the area, and the boggy land (possibly caused by the Walbrook) is part of the reason the building failed.

The word ‘bedlam’ comes from the hospital’s nickname, referring to confusion or uproar. At one stage, the hospital stood for everything wrong with asylums and mental health care.

Founded in 1247 as the Priory of the New Order of our Lady of Bethlehem on Bishopsgate, its goal was to collect alms to support the Crusades. By collecting taxes to cover the care of the poor, it became a hospital. Over time, it gained its association with mental illness.

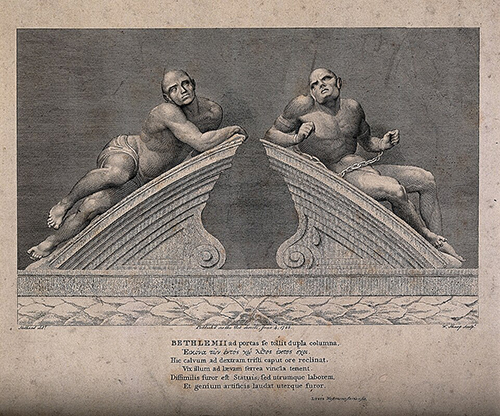

In 1676, the hospital moved to the London Wall site, famously a beautifully designed building. Before you get too impressed, remember that statues representing “Melancholy” and “Raving Madness” topped the gates.

Those in charge failed those in their care, using treatments best described as barbaric. They charged the public admission to view the patients, perhaps better described as inmates. Some argued the spectacle acted as a cautionary tale, while it was really financial exploitation of the vulnerable. William Hogarth immortalised the sorry state of the hospital in a scene from ‘A Rake’s Progress’ (1735).

The building, which had been built too quickly on poor land, was a mass of constant leaks and buckling walls by the end of the 18th century. The governors couldn’t cover the maintenance costs, and in 1815, the building closed. The hospital moved to a site in Lambeth, which is now the Imperial War Museum.

Narrow Streets

It’s difficult to follow the exact route of the Walbrook from here. It involves going down Throgmorton Avenue, a private road home to the carpenter and draper livery companies. The Walbrook once made its presence known here, with the land too wet for buildings, though that didn’t stop anyone from building a tower here in 1967. Demolished in 2007, excavations revealed the Walbrook channelled along a ditch in the avenue. This section yielded various archaeological finds, including animal bones, leather, and kilns, revealing plenty of industrial activity in the area (Bolton 2011: 125).

Archaeologists also found items in other parts of the Walbrook. A lot of metalwork came from the bed of its main stream. While one theory sees this as accumulated rubbish dumped in the river, Ralph Merrifield argued that Romans normally disposed of their rubbish in pits on their premises. Metalwork is rarely found in these pits, so why would they put it in the river instead (1995: 28). When I mean metalwork, the finds are impressive, including keys, knives, coins, rings, hair pins, spoons, and tools (Merrifield 1995: 32). There’s no real reason for them to be disposed of as rubbish.

Ritual Deposits?

Are they ritual deposits? It’s unclear. The tradition of offering metalwork to the gods using water is an Iron Age one, though there’s nothing to say people in Roman Britain didn’t continue the practice. Merrifield suggests they may have been used to replace the alternative material used in deposits: human skulls (1995: 36).

Excavations found human skulls in the Walbrook in the vicinity of Finsbury Circus, missing their lower jaws and the rest of the skeleton. The original theory saw them as young Roman men, massacred during the Iceni sacking of London by Boudicca. Carbon dating places them in the Roman period, although skulls from the Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age have also turned up (Merrifield 1995: 35).

The Roman skulls were most likely defleshed before they were deposited, given the lack of lower jaws. This raises questions about whether they could have been related to Boudicca’s revolt, because it would take longer for the heads to decompose enough for the jaw bones to fall away than the Britons spent in London (Marsh 1981: 94). It was unlikely anyone would have left decomposing bodies beside a water source, and there is little evidence of actual violence to the skulls. So the question remains about how they ended up in the river, and why (Marsh 1981: 95).

Back to the Route

We didn’t find any skulls, but we did get a little turned around in this section because of the network of narrow streets, but suffice to say, the Walbrook disappears beneath the Bank of England. That said, the street Lothbury that runs along the northern side of the bank is telling. It’s possible that the name comes from ‘lode’, meaning a channel leading to a stream (Bolton 2011: 126). You pass St Margaret Lothbury, a church beside which the Walbrook once ran.

Onto Walbrook

I got distracted wanting to see St Mary Woolnoth on Lombard Street, so again, we deviated from the route in Bolton’s book. We cut straight down Walbrook, the street presumably named for the river, beside the Mansion House. The river itself follows a parallel course to the street, a little to the west (Bolton 2011: 130).

The Temple of Mithras stands on Walbrook, although it’s perhaps more accurate to say it stands beneath the street. Accessed via the Bloomberg building, you head downstairs to the basement where you’ll find the ruins. Entry is, surprisingly, free, but I have an entire article about the Temple, so we won’t dwell on it too much here.

Still, it was good to revisit the temple having seen the Mithraeum at Carrawburgh on Hadrian’s Wall, which is far smaller!

At the bottom of Walbrook is a public artwork, inspired by the now lost river. Titled ‘Forgotten Streams’, artist Cristina Iglesias took her inspiration from the Walbrook. Water flows down sheets of bronze that are moulded to look like a river bed. It actually has three separate modes to mimic the flow levels of a tidal river, which is very effective. While the water does not come from the Walbrook, this is probably the closest we’ll come to imagining a river in the City.

The Last Stretch

After the excitement of the Mithraeum, the route wanders into the tangle of buildings on the other side of Cannon Street. You’ll find the London Stone in a shop front on Cannon Street, and I have an exclusive article for Patreon supporters all about it.

The route first follows Cloak Lane and then College Hill, originally known together as Elbow Lane. The Cutlers’ Hall on Cloak Lane belies the industry close to the Walbrook, and it was somewhere in this area in the late nineteenth century that someone found the head of a Roman statue in the river.

Passing down College Hill takes you past St Michael Paternoster. The original 13th-century church on the site burned down in the Great Fire of London, and Sir Christopher Wren oversaw the building of the church we see today.

In 1409, Dick Whittington paid for the rebuilding and extension of the church, and then he was buried there in 1423, although this tomb is now lost. Whittington also founded the College of St Spirit and St Mary at St Michael’s, though most people called it Whittington’s College. It relocated to Highgate in the 1820s, but also gave its name to College Hill.

Still No Walbrook

We crossed Whittington Gardens to follow Upper Thames Street, which marks the original line of the riverbank in Roman London. Across Upper Thames Street, we headed down Cousin Lane, which runs down to the Thames. A series of steps leads straight onto the foreshore, and we couldn’t resist having a wander around given neither of us had been that close to the Thames before. Plenty of oyster shells and animal bones lay among the stones and broken bricks on the shore.

The Walbrook actually discharges into the Thames further along, under the Walbrook Wharf walkway. Sadly, we didn’t get to see it, which seemed a fitting end to an expedition to follow a lost river.

Was it worth looking for the Walbrook?

For all it was strange to follow a river I never saw, it was still worth tracing the route. Following the Walbrook’s course took me to streets I would never have otherwise followed, and traced a path between important points in London’s history. Given its importance to the Romans, as a site of ritual deposits and industry, it’s not as well-known as it should be.

While this wasn’t strictly psychogeography, I feel the detours certainly added a bonus random element. The river thus connected sites that brought me closer to London lore, its Roman ritual past, and even darker periods of its history, like Bedlam.

I highly recommend London’s Lost Rivers: A Walker’s Guide by Tom Bolton, which traces the routes of seven rivers besides the Walbrook. Who knows which parts of London’s history you’ll rub up against?

Were you familiar with the Walbrook?

References

Bolton, Tom (2011), London’s Lost Rivers: A Walker’s Guide, London: Strange Attractor Press.

Draper, Steve (2013), ’91-101 Worship Street, EC2′, London’s Historic Shops and Markets, https://londonhistoricshops.blogspot.com/2013/09/91-101-worship-street-ec2.html. Accessed 22 April 2025.

Marsh, Geoff and West, Barbara (1981), ‘Skullduggery in Roman London?’, Transactions, Vol 32, pp. 86-102.

Merrifield, Ralph (1995), ‘ROMAN METALWORK FROM THE WALBROOK – RUBBISH, RITUAL OR REDUNDANCY?’, Transactions, Vol 46, pp. 36-44.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Have your say!