Much is often made of London’s lost rivers, like the Tyburn, Fleet, and Walbrook. Yet Newcastle upon Tyne also has rivers we cannot see. Ours are not lost, rather, they’re simply buried. The Skinnerburn, Erick Burn, Pandon Burn, Lam Burn, and Lort Burn all continue to flow beneath the city, down to the mighty Tyne.

The Lort Burn is perhaps the most well-known of the buried rivers. Originally called the Dene Burn, it gained its new name of Lort Burn in the late 14th century. Some sources say ‘Lort’ comes from an Old Norse word meaning ‘filth’ or ‘excrement’.

The Story of the Tyne: And the Hidden Rivers of Newcastle gives the rough route of the Lort Burn. I’ve followed it as best I can, given the current street layout, picking up the ghost stories and legends that lie along its route.

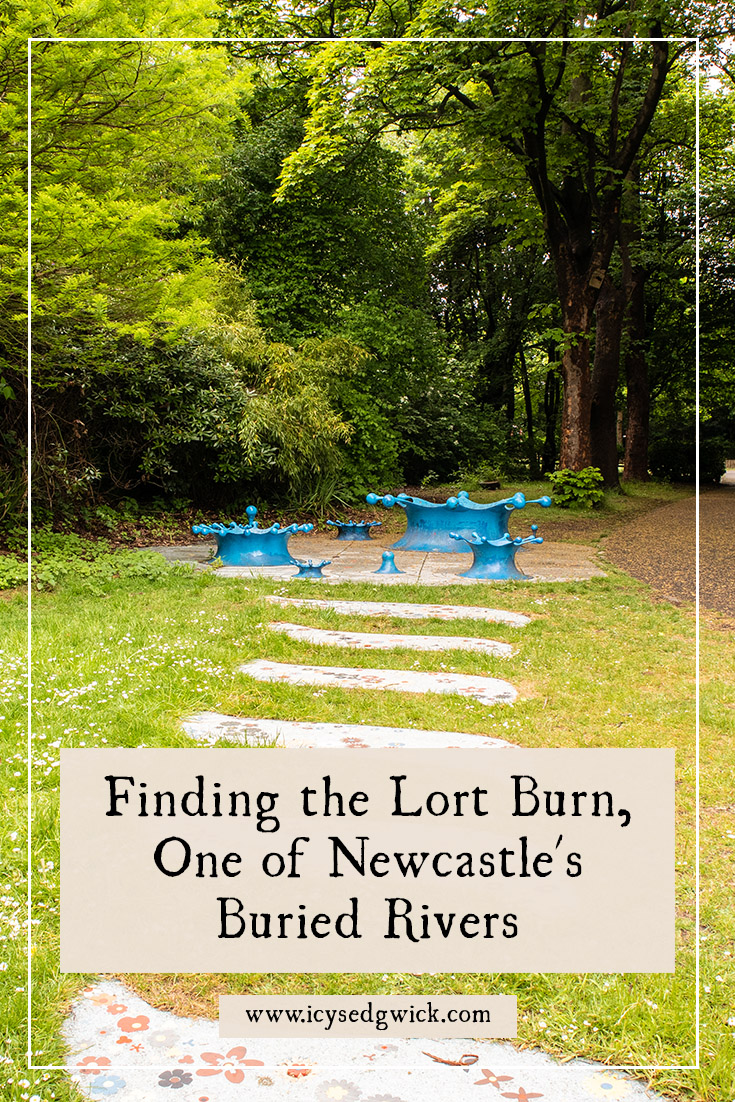

Leazes Park

Leazes Park is a green oasis of calm between the football fanaticism of St James’ Park to the west and the hubbub of the Royal Victoria Infirmary to the east. Newcastle’s first public park and Grade II listed, it opened in 1873.

The word ‘Leazes’ comes from an Old English word that meant pasture or meadow (Morgan 2007: 48).

As far as I can tell, the Lort Burn first rises underground somewhere in the vicinity of this sculpture.

The metal slabs inset with flowers mark the route of the burn from the sculpture down to the metal railings at the side of the lake. The flowers on the railing mark the point where the burn flows into the lake.

The slabs continue on the other side of the lake, showing the burn’s route as it flows out of the park and down Richardson Road.

St Thomas’ Street

Head down Richardson Road and turn left onto Queen Victoria Road. Next, turn right into St Thomas’ Street, built in 1842 (Morgan 2007: 48). I’ll be honest, it’s not a massively exciting street. At least its neighbouring street, St Thomas’ Crescent, was home to Pre-Raphaelite artist William Bell Scott for a while.

The route gets a little tangled up at the bottom of the street where it meets Percy Street. The shopping behemoth that is Eldon Square lies opposite the bottom of St Thomas’ Street, making it difficult to follow any exact route of the Lort Burn.

Blackett Street

I followed Percy Street west and then turned into Blackett Street.

According to Ken Smith and Tom Yellowley, the Lort Burn passed the Holy Well of St Bartholomew’s Nunnery in this area (2017). The Grainger Market now stands on the site of this nunnery, which explains nearby Nun Street’s name. Smith and Yellowley also explain that an earlier butcher’s market stood on the site of the nunnery over the burn (2017).

Tangent time! Monks and Nuns, and their Shenanigans

While Nun Street is a bit further over, the area is worth a slight tangent because it involves a secret tunnel! St Bartholomew’s Nunnery allegedly had secret tunnels to both Blackfriars and Greyfriars, although one of the ghostly nuns is seen walking at street level, which somewhat debunks the legend. But in this story, a Blackfriars monk and a nun fell in love. When she became pregnant, she was bricked up alive in the convent as punishment. Her ghost apparently wanders in Nuns Lane.

Blackett Street runs along the south side of Old Eldon Square. Only the original buildings to the east of the square remain, with the north and west sides demolished to build the shopping centre. The square has had several names over the years, with the Hippie Green and Goth Green being two of the most common, since the alternative community used to hang out here.

Old Eldon Square is also the site of a pretty funny story, dating to the time before the redevelopment of the area in the 1820s. This area was something of a wasteland, used as a rubbish dump and manure heap. One day, some workmen came to take some manure and unearthed a child’s body. They assembled a coroner and a jury, sure they would need an inquest to investigate. Luckily, the coroner was a surgeon, and when he examined the body, he discovered it was a wooden doll. It turned out that the former Theatre Royal manager had kept stage props in his house. When he retired, he’d dumped them all in the rubbish dump – and the doll had ended up in the manure heap! (Histon 2000: 39).

Back to the Route

I went through Eldon Square from Blackett Street to Clayton Street, then into the Grainger Market. It was nice to see it so busy for a change, even if I do miss Robinson’s the Bookshop and Scorpio Shoes.

For those who remember Robinson’s, it was originally founded in 1881. Yet there was a short period of a few weeks in 2000 when it seemed a ghost had popped by. The shop’s owner locked up every night, but found the stock had moved when he opened up the next morning. Some books even lay open, as if being read. While nothing went missing, it was clearly a weird experience. Even weirder, it stopped only a few weeks later. It has never been explained (Histon 2001: 19).

Grainger Street/Market Street Junction

Head out of the Grainger Market and turn left along Grainger Street to the junction with Market Street.

This marks the point where the Lam Burn, which begins somewhere under St Andrew’s Church, joins the Lort Burn. It’s difficult to figure out the route at this point because it apparently flowed over Nun’s Fields and past Anderson Place. The buildings in the area make this hard to follow.

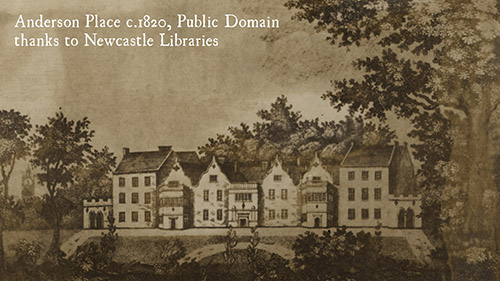

It’s also hard to picture it now, but a grand house once stood roughly where Lloyd’s Bank is now. Originally the site of Greyfriars, Robert Anderson bought the land in 1580 and built Newe House. Charles I spent time there under house arrest, although he was occasionally taken to Shieldfield to play golf.

According to legend, Charles tried to escape from Newe House in a boat down the Lort Burn. A ship waited for him on the Tyne. His escape attempt failed when he ran into a grille blocking the sewer into which the burn ran, and his captors recovered him. He allegedly haunts the Quayside, searching for his rescue ship (Histon 2000: 17).

Newe House passed through various hands until a new owner renamed it Anderson Place in 1801. Richard Grainger bought it in 1833 and demolished it to make way for his grand plans for the area.

Grey Street

Looking back up Grey Street, you’ll see Grey’s Monument. It honours Charles, Earl Grey, the only Northumbrian to be Prime Minister. He passed the Reform Act in 1832, which extended the electoral franchise, and the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833, which abolished slavery within the British Empire.

The statue also lost its head in 1941 after a lightning strike. It finally got a new one in 1947. Grey’s Monument has served as a lightning rod for activism in the city for decades, being the preferred location for protests and demonstrations.

More Ghostly Monks

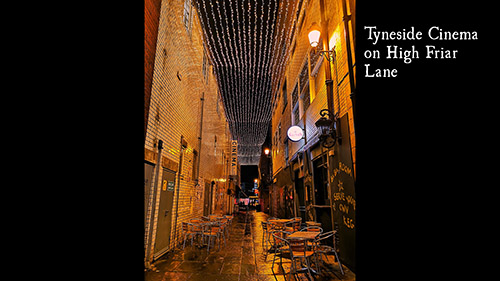

The area where the Monument now stands was once the site of Greyfriars, before Anderson Place. The Tyneside Cinema now stands on this parcel of land, and there are various reports of haunting in the cinema.

Cleaners described finding seats left upright suddenly folded down, and a figure in dark robes loitering in the corner. Others have seen a similar figure upstairs in the Electra, or even heard someone clearing their throat in an empty room (Histon 2000: 8).

When I was on a call to marketing staff at the cinema about an event, I suggested they include tales of the ghost. “The Victorian woman?” replied one of them. Clearly, there are several spectres at the Tyneside Cinema!

Onto Grey Street Itself

The Theatre Royal stands at the junction of Grey Street and Market Street. It opened in 1837, though it’s been extensively remodelled and restored since then. It’s also reputedly haunted by a Grey Lady, who I’ve talked about before.

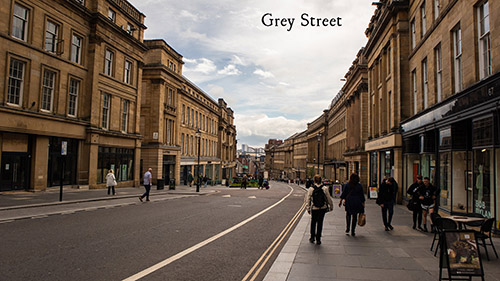

The sweep of Grey Street and down into Dean Street marks the approximate location of a deep ravine, or dene, that once cut Newcastle into two districts. The Lort Burn ran along this dene on its way to the Tyne below. Grey Street was built in the 1830s, originally called Upper Dean Street.

Richard Grainger intended Grey Street to be the main shopping street in the city. His plan saw the Central Station situated at the foot of the street. Unfortunately, they couldn’t level the land enough, so the station’s location moved to its present site on Neville Street (Morgan 2007: 54). Grey Street never quite became the shopping destination, but it’s often been voted Britain’s greatest street.

That’s despite the presence of the Lort Burn, although Grainger buried it to create Grey Street. The dene was deep enough that filling it in during the 1830s needed 250,000 cartloads of waste. This filled the 30ft necessary to level the site. The depth of the dene also helped to protect the Castle, since anyone attacking from the east would need to somehow cross the ravine.

The first of the dene’s two crossings was the Upper Dene Bridge, roughly where we find the street called High Bridge now. The Flesh Market was just south of the bridge, and people threw offal and other waste from the market into the burn here.

Mosley Street

The course of the Lort Burn follows Grey Street across Mosley Street and down Dean Street. Development in the area in the 1780s saw the creation of Mosley Street and Dean Street. Even by this point, people regarded the Lort Burn as a sewer, so burying it beneath the street probably brought some relief from the smell.

The strange dip in the road here is one of the few street-level indicators the Lort Burn is still here.

As an aside, Mosley Street was the first street in the UK lit with electric lighting. Joseph Swan, inventor of the lightbulb, worked at a shop on Mosley Street.

Dean Street

Partway down Dean Street, you’ll find a pair of staircases opposite each other on either side of the street. One is marked Low Bridge, and marks the site of the bridge over the Lort Burn, sometimes called Nether Dean Bridge. Now, the stairs take you up onto Pilgrim Street. The Nether Dean Bridge was removed in 1787.

The Tyne is tidal, and the tide flowed up the Lort Burn as far as Low Bridge. Some sources suggested it even flowed as high as High Bridge, and merchants used small boats to reach the old nearby Flesh Market.

My mum remembers an old phrase, “when the ship sails up Dean Street”, used as a response to children who asked for unlikely things. While it might have been used as a form of irony, clearly at some point, ships did sail up here…at least before it was Dean Street!

A Detour for the Vampire Rabbit

The other staircase is Cathedral Stairs, which leads between Cathedral Buildings and Milburn House to the back of St Nicholas’ Cathedral. Turn to your left at the top of the stairs to see the bust of Thomas Bewick.

This famed engraver and natural history author spent a lot of his career (1767 – 1825) in his workshop here. We met him in the cows in folklore episode, thanks to his engraving, ‘The Wild Bull’, featuring one of the Chillingham Cattle. He’s best known for A History of British Birds, and he was actually an early animal rights campaigner and anti-war proponent.

If you turn right at the top of the stairs and follow the back of Cathedral Buildings, you’ll find our old friend the Vampire Rabbit over the central rear entrance. Hurray!

Heading back down Cathedral Stairs takes you back onto Dean Street. On the left, between Brew Dog and what used to be Pizza Express, you’ll find another staircase. This is Painter’s Heugh, which marks a stopping point on the Lort Burn. It’s believed the name refers to mooring ropes known as painters.

The Side

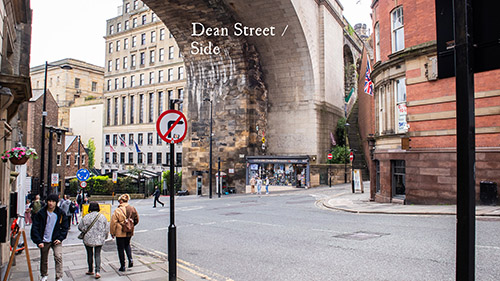

Dean Street meets the Side just below Painter’s Heugh. The junction also marks the point where a small burn that begins at Blackfriars meets the Lort Burn.

You’ll also see Dog Leap Stairs rising up along the side of the railway bridge, which leads to the Castle Garth area. Despite the name, it has nothing to do with jumping dogs. It actually derives from ‘Dog Loup’, meaning ‘a narrow slip of ground between houses’ (Sitelines n.d.).

Follow the Side east past the Crown Posada, and the road eventually leads into Sandhill. Another smaller bridge crossed the Lort Burn at the bottom of the Side. In 1648, musicians allegedly played on the bridge to entertain Oliver Cromwell.

Sandhill

Sandhill is so-named for the mound of sand left by the tide where the Lort Burn met the Tyne. The city culverted the lowest reaches of the burn in 1646, and waste dumped into the Tyne created landfill so they could build on the reclaimed land.

It hosted a market selling cloth, leather, fish, herbs, and bread (Histon 2006: 16). Sandhill was also a popular destination to see bull baiting or public executions.

Sandhill is actually the site of a love story that’s become a legend, despite being surprisingly rooted in fact. Aubone Surtees lived at No. 41 Sandhill with his family, and hoped for a good match for his daughter, Bessie. After all, he was a banker, so he felt she should marry someone appropriate.

But these stories rarely work out like that, and Bessie had met John Scott, the son of a coal trader. Surtees refused to give his permission and forbade Bessie from seeing Scott. Bessie decided to throw caution to the wind and, in 1772, climbed out of the first-floor window. Scott waited on a horse below, and the pair galloped away to elope. The legend part of it kicks in when the story claims Scott rode up Dog Leap Stairs, which I find unlikely given how steep and narrow they are.

Did Bessie and Scott live happily ever after? Surprisingly, yes, they did. Scott even launched a successful political career and ended up Chancellor of England, becoming Lord Eldon in the process. For those familiar with Newcastle and its shopping centre, his name is where we get Eldon Square from.

The Guildhall

The Lort Burn runs under Sandhill and then the Guildhall before it discharges into the Tyne somewhere nearby. In 1296, someone built a 135ft galley ship at the mouth of the Lort Burn at a cost of £205. It marks Newcastle’s earliest recorded shipbuilding endeavour (Co-Curate, n.d.).

A civic building has stood on the Guildhall site since the medieval era. The current building dates to the 1650s, but was refaced 150 years later, giving it its Georgian aesthetic.

It’s also apparently haunted.

One of the more famous phantoms is that of Jane Jamieson, a fish hawker and murderess. On New Year’s Day in 1829, she’d been out drinking with William Ellison, but they ran out of money. Jamieson demanded money from her mother, who lived at the Keelmen’s Hospital on City Road. Her mother refused, and an argument broke out, which ended when Jamieson grabbed a poker from the fire and stabbed her mother.

The trial took place at the Guildhall. Jamieson tried to claim Ellison kicked her mother to death, but the evidence pointed to Jamieson. She eventually admitted she might have done it, but was too drunk to remember. Her execution drew a huge crowd, perhaps because she was the first woman publicly hanged in Newcastle for 71 years (Histon 2001: 42).

After the execution, her body was used as a teaching aid at the Barber Surgeons’ Hall. Yet according to legend, people heard a disembodied voice crying out one of the typical street traders’ cries near the Guildhall. No one knows why this would be Jamieson, since she was a fish hawker and the song was that of a fruit seller. Yet the song ended with “Bring Billy Ellison to me”, which apparently gave Jamieson’s identity away (Histon 2001: 44).

The Guildhall currently stands empty after the departure of the Hard Rock Cafe. But who knows how empty it really is?

Was it worth looking for the Lort Burn?

For all it was strange to follow a river I never saw, it was still worth tracing the route. While I know the city centre well, navigating it while following the Lort Burn’s course gave me a different perspective on the streets and how they connect to one another.

This form of psychogeography, following a buried river to encounter the city above, provides a window into that city’s history. While this didn’t take me into the Roman or Saxon history of the city, it did help me to uncover more about the medieval, Georgian, and Victorian incarnations of Newcastle. The river provides the throughline to take a wanderer through that history.

Were you familiar with the Lort Burn?

References

Co-Curate (no date), ‘Lort Burn’, Co-Curate, https://co-curate.ncl.ac.uk/lort-burn/. Accessed 27 May 2025.

Histon, Vanessa (2000), Nightmare on Grey Street: Newcastle’s Darker Side, Newcastle upon Tyne: Tyne Bridge Publishing (affiliate link).

Histon, Vanessa (2001), Ghosts of Grainger Town: Further Tales from Newcastle’s Darker Side, Newcastle upon Tyne: Tyne Bridge Publishing (affiliate link).

Histon, Vanessa (2006), Unlocking the Quayside: Newcastle Gateshead’s historic waterfront explained, Newcastle upon Tyne: Tyne Bridge Publishing (affiliate link).

Sitelines (no date), ‘The Side, Dog Leap Stairs’, Sitelines, https://sitelines.newcastle.gov.uk/SMR/9916. Accessed 2 March 2025.

Smith, Ken and Yellowley, Tom (2017), The Story of the Tyne: And the Hidden Rivers of Newcastle, Newcastle upon Tyne: Tyne Bridge Publishing (affiliate link).

Morgan, Alan (2007), Victorian Panorama: A Visit to Newcastle upon Tyne in the Reign of Queen Victoria, Newcastle upon Tyne: Tyne Bridge Publishing.

Nutty about folklore and want more?

Add your email below and get these posts in your inbox every week.

You'll also get my 5-step guide to protecting your home using folklore!

Have your say!